Today, I’d like to recommend this book to everyone who wants to learn about editing.

Bryan Furuness and Sarah Layden. The Invisible Art of Literary Editing. London. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2023. 152 pages.

The Invisible Art of Literary Editing serves as a beginner’s guide to the job of an editor: their daily responsibilities, approach to authors and manuscripts, and essential skills. The authors, Bryan Furuness and Sarah Layden, state in the Introduction that the art of editing is challenging to learn because the editor’s goal is to remain out of the spotlight and let the author shine instead. This book takes its reader through the editing process as a mentor would during an apprenticeship and encourages independent learning based on practical exercises —a mini self-internship.

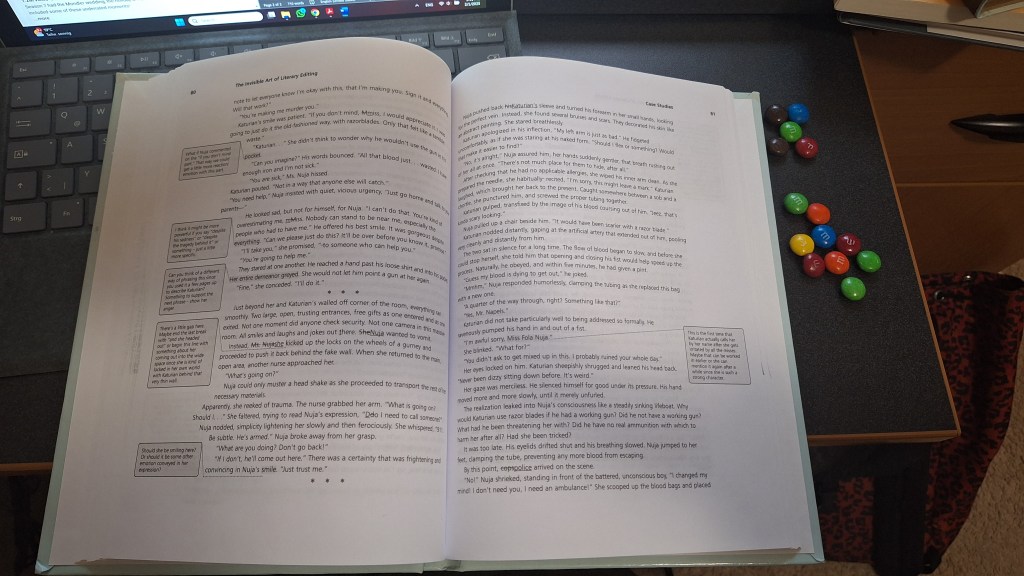

The book covers the editing phase aiming for excellence, which includes acquisition, global editing, and line editing. It comprises six sections: Aesthetic; Acquisition: From Attraction to Acceptance, from Solicitation to Slush; Responding to Submissions; Correspondence; Case Studies; Test Editing: From Observation to Practice. Each section starts with a discussion part offering some tips, moves to show some real-life examples, and ends with practical exercises and questions encouraging critical thinking. The examples showcase the editing process from a manuscript with the editor’s comments to the final published version. The Case Studies section contains interviews with professional editors and undergraduate students learning the craft.

The book is concise, and its conversational tone makes it easy to read. It doesn’t bore the readers or get them stuck with a complicated passage; everything is straightforward. There are many opportunities to engage deeper with the book by doing independent research, answering questions for consideration, and practicing on dummy texts provided in the appendix. There are many opportunities to self-reflect and compare your editing with the work of more experienced editors.

As a novice editor, I find some of the book’s tips valuable and enlightening. It encourages the reader to pay attention to details one might take for granted and overlook. Moving forward into the book, however, I wished there were more straightforward tips and suggestions before the practical examples. It is a short book, and although this feature can be viewed as an advantage, it feels even shorter because the final versions of edited manuscripts, essentially the same text repeated twice, take up a lot of space.

Despite its brevity, the book showcases editing in various genres: short creative non-fiction, short fiction, novel excerpts, and even some poetry. The case studies interview professional editors, including Julie Riddle, Valerie Vogrin, Maggie Smith, and Mark Doten, who share their styles and approaches to their craft. The authors compare this section to the surgical theater, in which medical students observe the surgeon doing their job. Comparing your process as a beginner with an experienced editor can make readers more confident about their future editing choices. The editors also discuss their approach to communicating with writers and incorporating diversity, equity, and inclusion into their practices. The latter, in particular, is rarely revealed in detail by editors, although it is a heated topic among the writers.

The book is also helpful to writers seeking to understand how publishing works. Writers can learn to differentiate between a novice and a professional editor, correctly interpret the editor’s intentions in correspondence, and even survive the slush pile. For example, the Acquisition section gives editors tips and tricks on writing a call for submissions that attract authors that match the magazine’s aesthetic and mission. Writers can learn to determine whether a publication is worthy of submission and, therefore, the writer’s time and effort. In addition, every writer deals with editing in a specific capacity, so seeing what editors mercilessly cut out of the manuscript or find hard to work with can help writers submit cleaner texts. Editing with Lenses, a sub-section of Test Editing, is particularly helpful. This part suggests that one should limit oneself to one aspect of editing during each reading. Adopting this attitude can help many writers navigate the anxiety of the tedious labor of editing.

Overall, it is a great starting point for beginners like myself who want to learn the terminology and go a little beyond the surface of common knowledge about the publishing world.

Have you read the book? Would you like to? Let me know what you think!